What Do You Do When Your Body Makes No Sense?

A Four-year-old's Perspective on Illness

[I wrote this post three years ago or, in pandemic years, three lifetimes.]

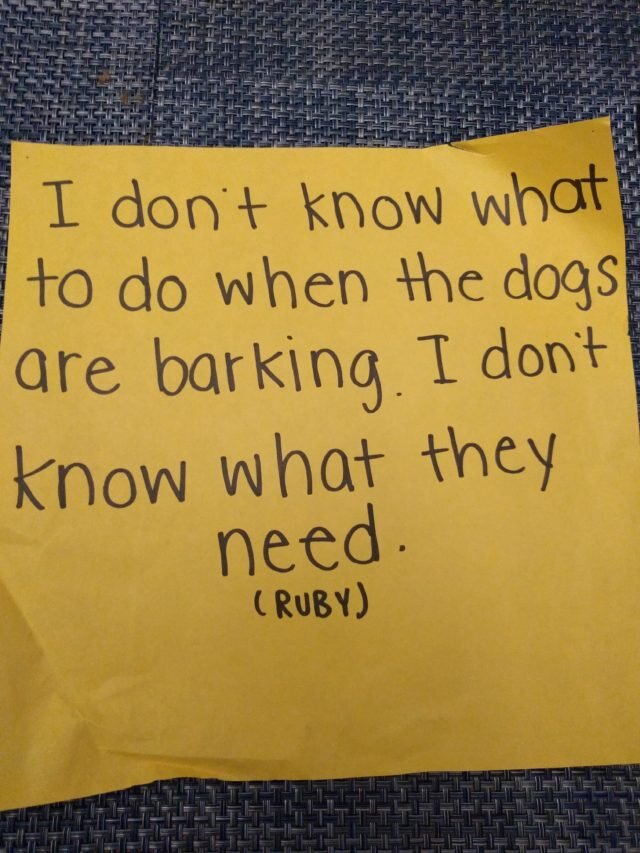

Last week, I discovered this handwritten message that had been taken off the wall of my daughter’s Pre-K classroom. My daughter had said these words during a classroom meeting when her teacher wanted to know why a “Doggy” game had led to so much arguing and crying.

As far as the game, I think you get the idea: the kids take turns acting like a dog, crawling on the floor, rolling over, barking, and sometimes being sick and needing to be taken care of. To be an “owner” was more responsibility. You had to lead the dog on walks around the room, give it imaginary treats, and most challenging of all, decipher what the hell all the various panting, barking, and paw-shaking meant.

My daughter didn’t like to be the owner, and most kids didn’t either. This was part of the friction within the game. It was more fun to bark and lay on your back with your hands and feet in the air than it was to have to meet someone else’s needs. During the class meeting on the rug, the teacher asked students what was upsetting them about the game. My daughter said, exasperated, “I don’t know what to do when the dogs are barking. I don’t know what they need.”

My mind stopped when I read this. In two sentences, she captured my decades-long struggle to understand and deal with my body.

I could relate.

I don’t know what to do when it’s barking.

I don’t know what it needs.

As many of you know, I’ve experienced chronic pain and sizable physical limitations at times. I know that when our body or emotions feel out of control, there is such pressure to understand exactly what’s going on. That pressure partially comes from within, since we want to feel better and hope that we can correct the problem. The pressure also partially comes from outside us; well-meaning friends continually ask us if we’ve figured out what’s wrong with us. You're still not better?

Yet, who can say with any real confidence what the various aches, tensions, and emotional surges in our body really mean? We are all playing owner with our body: trying to understand what it needs and when to take it for a walk. But it's hard to embrace the mystery. Especially for people like me, in the “wellness” field – we act like experts. As if we too aren’t fumbling around in the dark much of the time.

What happens is that we spend a lot of time dwelling in the past (when exactly did I screw this up?) and the future (how do I get out of this?). Trying to think our way out of the situation is seductive, though spending increasing amounts of time in our own head only isolates us from others. Yet, there is another possibility.

Not Knowing Can Lead to Openness

We can learn to remain in the vulnerable place of accepting a mystery and not criticizing ourselves for it, but rather understanding that this is just the way it is, right now. We can not know and that’s okay.

What my daughter channeled during carpet time is a centuries-old school of Korean Zen Buddhism known as “Don’t Know Mind.” This tradition emphasizes a mental state of complete openness where one isn’t grasping for answers or certainty. For example, I don’t know what my spouse needs right now, but I’m going to remain open and not grasp for easy answers or shut down.

Or, as my neurologist once told me when I was pressing him to try and give me a diagnosis, “Be careful what you ask for. If you keep pushing a doctor for a diagnosis, they may give you one but it might not be the right one.”

From the perspective of working with our bodies, it’s not that having an answer or solution is bad. It’s that we tend to stop looking and noticing when we “know.” For instance, if I'm absolutely certain how to hold my body when I'm sitting there's no awareness or curiosity about how sitting actually feels. I've checked the mental box labeled "sitting" and can move on to whatever my next preoccupation is. But Don't Know mind encourages us to ask constantly: What is this moment really like? Maybe I'm not so sure I know. Maybe I can actually just observe for a moment without any expectation.

Not Having to Know Can Lead to Gentleness

It’s frustrating to not know what our body or mind needs. What we tend to do is cycle, endlessly, through various strategies – ranging from fixing to numbing – thereby fatiguing and depressing ourselves in the process. We would do anything other than be kind to ourselves. Yet it’s not until we recognize our own not knowing, until we acknowledge our own lack of certainty, and touch our own fear, that we can begin to be gentle towards ourselves and others. When we stop trying to fix ourselves there is room for kindness to arise. We can be kind to ourselves even if we don’t have a clue, even if we feel like we don’t deserve it. Eventually, it dawns on us that other people, too, are grasping for answers. They have their own dogs barking to contend with.

It has taken years of meditation, therapy, working with hundreds of students, and mucho disappointment to get to a place where I might (someday) be able to express something as simple and without blame as my daughter did. If I had been there with her in the classroom, I would’ve knelt down and given her a hug and said, “I don’t know either.” And we could both start, with kindness, from there.

A short practice :

Sometimes when my neck goes out and part of me keeps trying – without success – to find a comfortable position, I tell myself, “I don't have to know how to hold my neck.”

“I don't have to to know what to do.”

Saying this kind of intention helps me find more space and possibility. It stops the restless search for relief based on some limited repertoire of movements or positions that feel right. Instead, I’m able to let go of trying to micromanage my body and there's usually a release.

When you're feeling stuck, physically or mentally, try offering yourself an intention along the lines of, I don't need to know what to do right now. Try doing this several times, and you may find that you're not confined to the same old choices over and over.