"People, Not Principles"

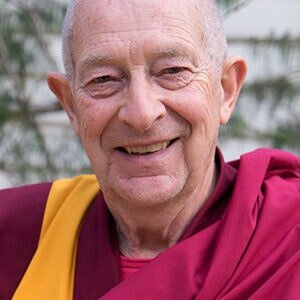

And the monk who empowered me.

Join me tomorrow night, Tuesday, for a public talk titled, "Your Body Is Your Practice," hosted by the Shambhala Center of NYC.

The first person to teach me meditation was a towering Australian named Thubten Gyatso. He was living in Mongolia, as I was in the spring of 2003, and he just happened to open the door at the Federation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition (FPMT) when I came knocking one afternoon. He was wearing the crimson and gold robes of a Buddhist monk and the sight of his bare arms took me back. I was used to seeing men in sleeveless shirts as a display of muscle and power but Thubten’s arms were pale and unconditioned. Ostensibly, I was there because I needed to do a report on a non-profit in Ulaan Baatar, but secretly I wanted to get the goods on Buddhism. For the latter, Thubten advised me to attend an introduction to meditation class later in the week.

I returned and joined 20 to 30 other aspirants in the shrine room where I endeavored, like the world’s stiffest kindergartner, to sit cross-legged on the floor. I assumed this contortion would be the first requirement of spiritual development – acting like you are fine when you’re not. Thubten took his place at the front, folding his lower limbs like tent poles beneath his robes. Halfway through his talk, an adopted black cat sauntered down the aisle and climbed into Thubten’s lap where it sat for the remainder. I can’t remember a thing he said but there was something about him, the quiet of the center, and the testimony of the cat that kept me coming back to the FPMT every few days after school.

I was ‘working through stuff.’ My previous semester at college, I had slept on a mattress on the floor of my undecorated dorm room. And it had recently become clear through letters from back on campus in Connecticut that my girlfriend and I were not going to last. And so, I came to share this moment of my life with a celibate stranger. At night, I’d go dancing at nightclubs with my classmates, claiming “Cotton-Eyed Joe” as our nostalgic American anthem and then, the next afternoon, I’d have tea with Thubten and borrow texts like Make Your Mind An Ocean. I presented myself as an even-keeled surveyor of knowledge and philosophy rather than as a young person who was struggling to feel okay. I understood as much Buddhism as the cat but I, too, had grasped that it felt good to be around the man.

Also in that spring of 2003, Mongolia had joined the “Coalition of the Willing” in the invasion of Iraq. Despite being so far away, the war was a topic of great interest among native Mongolians and expatriates. Ideological positions were debated in bars, newspapers, and among herders on the steppe. In the middle of this, Thubten penned an op-ed for the English language newspaper titled, “People, Not Principles.” He made a pithy interpretation of Buddhist philosophy, saying that when we become convinced of our righteousness we stop seeing the humanity in others.

Near the end of my semester, I decided I would attempt a two-week solitary retreat in a historic cave in the Gobi Desert. Thubten gently tried to dissuade me from doing a solitary retreat (in a cave!) with only a few months of meditation experience. But he could also see I was hungry for adventure. In this, me and the quiet monk were kin. Before being ordained, he was a physician and had traveled through Afghanistan and Iran by motorcycle in the 1970s and sailed down the Indus River on a handmade boat. What he told me before I left, I’ll always remember: “When you go on retreat, it’s like taking the lid off the garbage can.” He knew that many of the things I would not want to see or feel would arise. He spoke with authority, having conducted a three-year solitary retreat in the Australian bush.

What he didn’t say was that Buddhism would cure this. He did not offer a four-step practice, promise, or an online course that would rectify the contents of the garbage can. He listened to me, answered my questions as best he could, and would occasionally lend me a book or give me some meditation advice, but never with the promise that this would cure all that was hurting me. Despite being an ordained monk – or because of it – he had no delusions of Buddhism as a saving vessel. I’ve come to respect Thubten so much for everything he didn’t say to me. I have a pair of uncles who used to slip pamphlets from their born-again church into my birthday cards, informing me of damnation upon homosexuality or salvation upon accepting Jesus Christ as my Savior. What killed me was the casualness of their advice – they barely knew me but believed they had all the answers on a piece of paper.

Obviously, Buddhism was an important framework for Thubten but he was able to let it all go with me and give me what I needed, which was not a fake promise or easy answers, but respect and gentleness toward all my incurability.

The venerable Thubten Gyatso’s most recent book is A Leaf in the Wind.